MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE BOOK

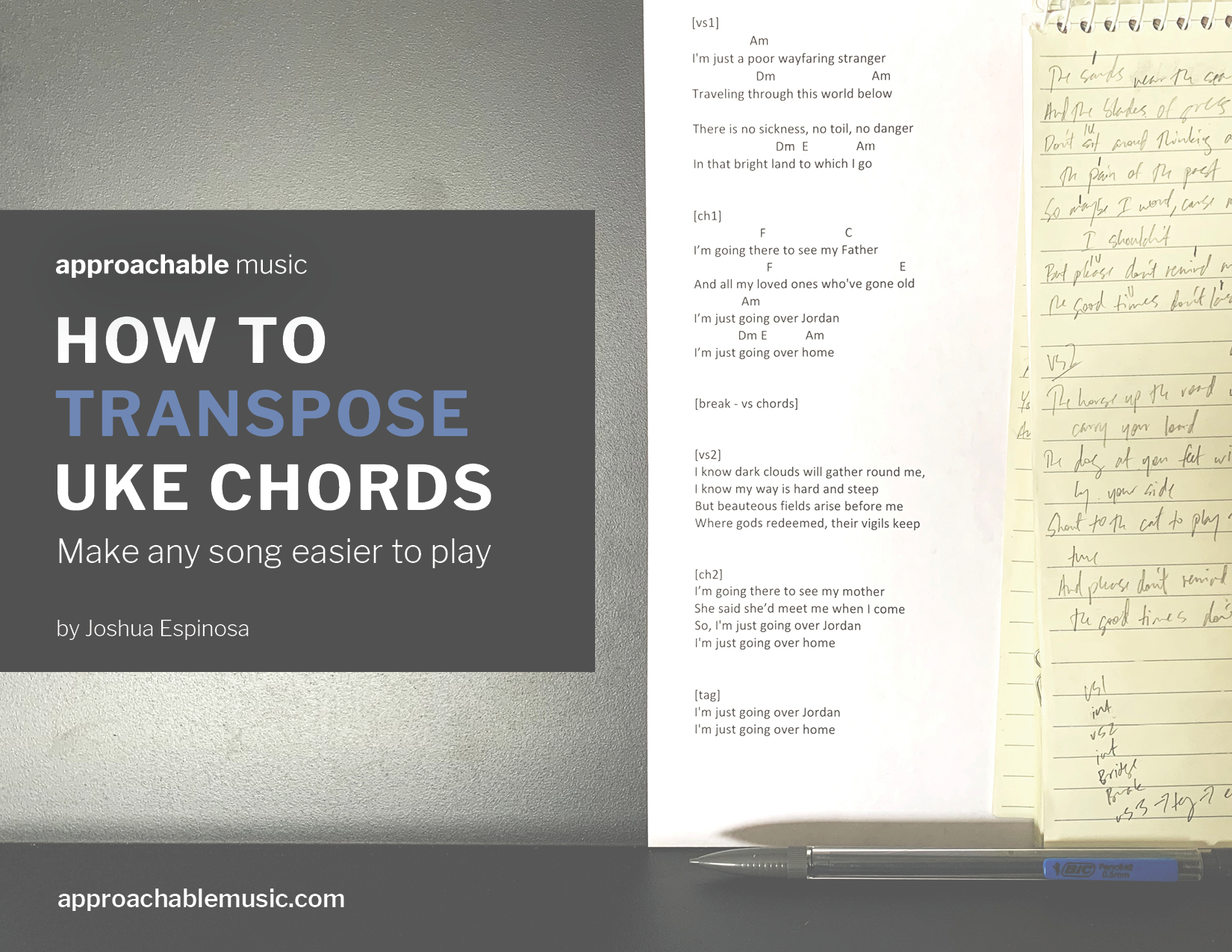

In this book, you'll learn how to transpose ukulele chords. Ukulele players come across songs all the time that use chords they'd rather not play. But while a beginner player might look for a different version of the song, an experienced one would probably just change the chords. The process of changing song chords is called transposing, and every ukulele player worth their salt should know how to do it.

The ability to transpose allows you to change any song to use chords that either work best on the ukulele or are simply, easier for you to play.

The catch is that to learn it, you have to understand a few music principles, and I get it — learning music theory might sound like a major turn off. But hear me out: would you rather have playing music be a little harder on your brain, or a lot harder on your hands?

Most of the heavy lifting when it comes to gaining the ability to transpose song chords is gaining an understanding of how we organize chords in music theory. So, let's take this part all the way from the ground up.

Scientifically, there are an infinite number of sounds possible on earth. But somewhere in human history, someone chose 12 particular frequencies — known as pitches — and gave each one a name.

The Chromatic Scale

Named pitches are called notes, and those 12 notes are the foundation of music. At this point, you should know that when musicians say "music," they mean "Western music," as there are some cultures that use notes beyond the 12 parent notes as their foundations. But for all intents and purposes, Western music is simply, music.

Any collection of notes is called a scale, and the set of 12 parent notes is called the chromatic scale. Basically, the notes in the chromatic scale are named alphabetically, from A to G, with a little variation in between some of the letters.

These are the essential things you need to know about the chromatic scale. The "#/b" is pronounced "sharp/flat," so A#/Bb is said, “A sharp/B flat.” Notes separated by slashes have the same sound (or pitch), but two different names. What you call it depends on context. For example, when you see A#/Bb, it means that A# and Bb sound exactly the same, and as such, are played exactly the same way on an instrument. The note is called one or the other depending on the situation. For now, just think of the note as "A sharp/B flat" in its entirety, and leave it at that.

Moving one note in either direction is called moving a half step. So, going from A to A#/Bb is one half step. So is going from C back to B. Moving two consecutive notes in either direction is called a whole step. So, going from A to B is one whole step. So is going from C back to A#/Bb. Anytime you move toward the right, you are moving "up" the scale, which produces a more shrill, or higher-sounding pitch than the previous note. If you go toward the left, you move "down" the scale and produce a deeper, or lower-sounding note than the one you came from.

The chromatic scale is an infinite loop either way. As you go up the scale, when you hit G#/Ab, the next note is A again and the loop starts over. If you're going down the scale and hit A, the next note is G#/Ab. There is no H note.

You can start the loop of the scale from any note. Just remember that when you hit G#/Ab, the loop flips over to A. For instance, you might see the scale written like this: C C#/Db D D#/Eb E F F#/Gb G G#/Ab A A#/Bb B. Take special note of what happened after G#/Ab.

Keys

Each note on the chromatic scale has two unique "sounds" associated with it. Each "sound" is called a key and is made up of various musical elements — one of which being a specific set of chords that sound good when played together.

One of the two keys associated with a chromatic scale note is called a major key, and the other is called a minor key. In all, there are 34 total keys, two for each note on the chromatic scale. Since they are considered separate in music theory, notes separated by slashes are counted as one each.

Each one of these 34 keys has a specific chord set attached to it, and understanding how the chord sets are structured as well as how they relate to each other is critical for being able to transpose song chords.

Songs are typically built with 3-5 chords from the chord set that's attached to one specific key. When musicians say a song is written

in the key of G, for example, they mean that the song uses a few chords from the chord set attached to the G major key.

It's important to note at this point that almost always, the "major" part is implied, but never the minor. So, if someone says you're in

"the key of G," you're always in G major. They have to specifically say you're in "the key of G minor" to actually be in G minor.

Here are some other things you need to know about the chord sets in each key. Each chord set in each key is comprised of seven chords, numbered one through seven as Roman numerals. Each chord set also includes the same combination of chord types: three chords are major chords, three chords are minor chords and one chord is a diminished chord, which is a type of chord that's much less common than the major or minor ones.

Major chords are always numbered with uppercase Roman numerals. Minor and diminished chords are always numbered

with lowercase Roman numerals. The first chord in the set always coincides with the name of the key. So, in the key of G, the first chord is a G major chord (remember, the term "key of G" implies a major key). The first chord in the key of G minor is a Gm chord.

Chord sets have an alphabetical structure. From the first chord, the rest of the chords in the set fall in line alphabetically

using the musical alphabet — remember, essentially, after G everything flips back over to A.

In the key of G, G major is the first chord because it coincides with the name of the key. The second chord has to be some kind of A because A comes after G in music. It really doesn't matter at this point whether the chord is major, minor or diminished or even whether it's sharp, flat or neither. All you need to understand at this point is that it's some type of A. The third chord is the same thing — some type of B, then some type of C, all they way to the seventh chord, which is some type of F.

It's really important to get a handle on all of these chord set rules because they're the keys to not only being able to transpose song chords, but also to the formulaic, numerical and alphabetic nature of music theory as a whole. Realistically, if you can get this stuff, other music theory principles won't seem like such a reach.

Major Keys

Songs written in major keys are bright and happy sounding. In major key chord sets, the one (I), four (IV) and five (V) chords are always major chords. Also remember that the one (I) chord always coincides with the key name. The two (ii), three (iii) and six (vi) chords are always minor chords. The seven (vii) chord is always a diminished chord ("dim" for short).

For example, the key of A starts with A major as its one (I) chord. This meets both criteria for one (I) chords in major keys: it's a major chord, and it coincides with the name of the key. The ii and iii chords, which are always minor, are Bm and C#m. Alphabetically, that works as B and C follow A. At this point, you might wonder how to figure out whether a chord is sharp, flat or neither, but realistically, it's easiest to simply look up the sharps and flats in each key. There's not really a more intuitive solution.

Keep going, and find that the IV and V chords are both major and also work alphabetically. Then, the vi is minor and the vii is diminished — all simply following the rules for their slots.

Finally, notice all the overlap between keys. For instance, the Bm is the ii chord in the key of A, but it's also the vi chord in the key of D. Overlap is a common in music because there are only so many notes on the chromatic scale.

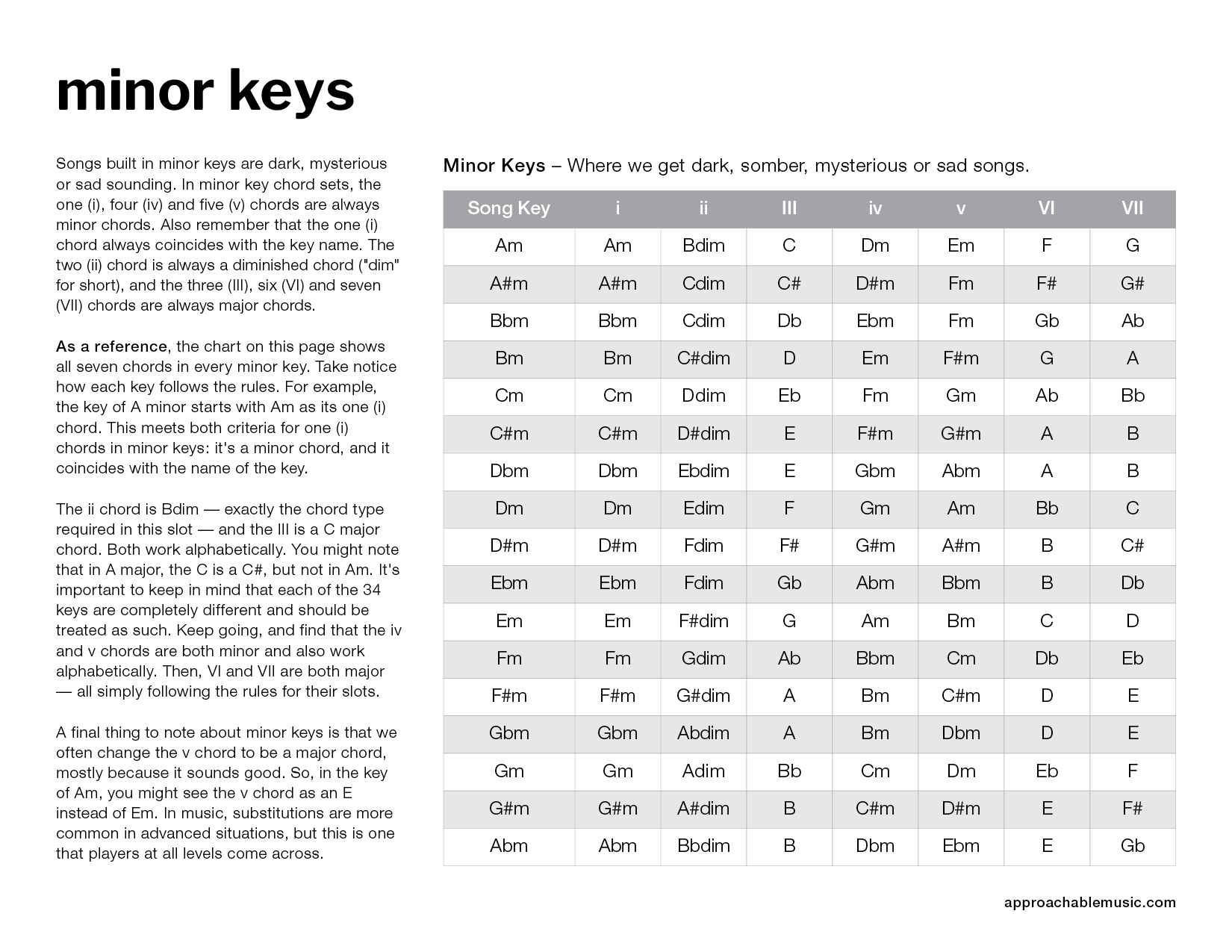

Minor Keys

Songs built in minor keys are dark, mysterious or sad sounding. In minor key chord sets, the one (i), four (iv) and five (v) chords are always minor chords. Also remember that the one (i) chord always coincides with the key name. The two (ii) chord is always a diminished chord ("dim" for short), and the three (III), six (VI) and seven (VII) chords are always major chords.

For example, the key of A minor starts with Am as its one (i) chord. This meets both criteria for one (i) chords in minor keys: it's a minor chord, and it coincides with the name of the key.

The ii chord is Bdim — exactly the chord type required in this slot — and the III is a C major chord. Both work alphabetically. You might note that in A major, the C is a C#, but not in Am. It's important to keep in mind that each of the 34 keys are completely different and should be treated as such. Keep going, and find that the iv and v chords are both minor and also work alphabetically.

Then, VI and VII are both major — all simply following the rules for their slots. A final thing to note about minor keys is that we often change the v chord to be a major chord, mostly because it sounds good. So, in the key of Am, you might see the v chord as an E instead of Em. In music, substitutions are more common in advanced situations, but this is one that players at all levels come across.

How to Transpose Ukulele Chords

Once you have a grasp on how chord sets work, changing song chords from one key to another is pretty straightforward. First, find out the original key of the song you want to transpose by identifying the last chord of the song — not the first — as your key name and hence, your one (I) chord.

Now, it's not always 100% that the ending will give you the key, but it's pretty close. If something doesn't sound right, look at the song chords as a whole and choose whichever key has the most chords in common with it.

Then, choose a new key and replace every chord in the song's original key to the corresponding chord in the new key.

So, if your song is originally in A and you want to change it to use chords from the key of C, every instance of the A chord will become a C because as A is the one (I) chord in the key of A, so is C the one (I) chord in the key of C.

Any and all Bm chords, the two (ii) chord in A, would become Dm chords, the ii in the key of C, and so on, until all the chords are changed.

The same rules apply if you were going from one minor key to another — change all the original chords to its corresponding chord in the new key. Note that you can't change a major key into a minor key or vice versa.